It’s an uncertain time: data firm S&P Global reports that UK private sector activity growth slowed in September, across both services firms and manufacturers. Companies, they reported, are taking a “wait-and-see approach” to decision-making ahead of the Autumn Budget, putting their investment plans on ice.

But beyond the budget, there are other uncertainties: commentators everywhere are declaring the next Industrial Revolution, as AI increasingly finds its way into all aspects of life – from the doctor’s surgery through to the battlefield.

There is also the problem of rising national debt, both here in Blighty and across the pond: the US has as much federal debt now as it did at the end of WWII, and the Congressional Budget Office projects debt will grow exponentially – leaving it (and us) highly vulnerable to the next recession, crisis, war or pandemic.

Amidst so much turbulence and uncertainty, how can companies even begin to fathom big investment strategies like M&A?

Acquiring during downturns

“The time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets”

If the global financial crisis taught us anything – besides the danger of deregulation – it is that “the time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets”.

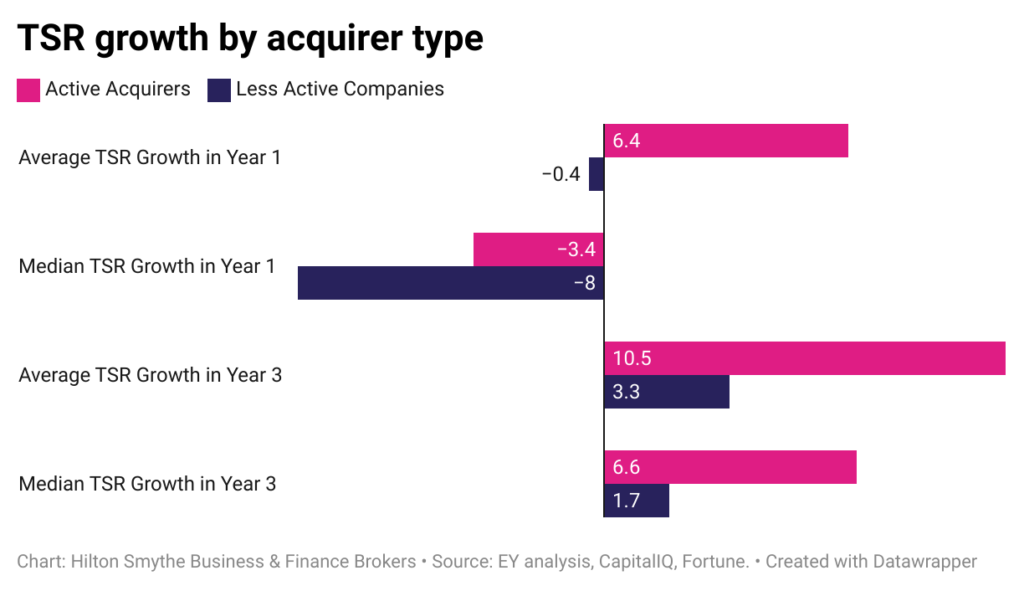

Companies that made significant acquisitions during that economic downturn ended up outperforming those that did not. Those companies that made acquisitions totalling at least 10% of their market cap from 2008 through 2010 had average total shareholder returns (TSR) of 6.4% from January 2007 through January 2008, compared with TSR of 3.4% for less active companies, according to EY analysis.

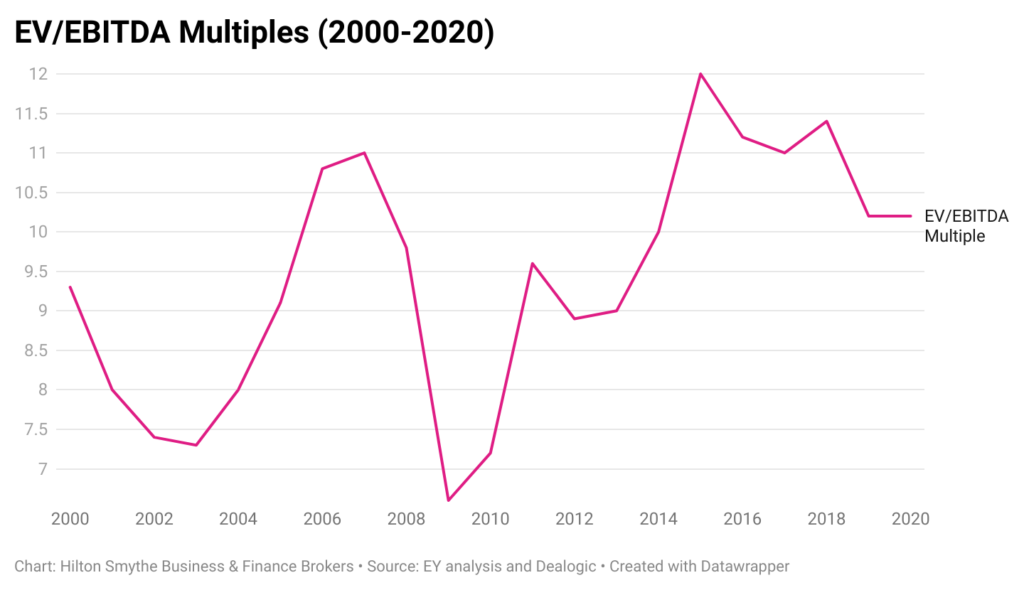

Companies acquiring during this time also benefitted from lower EBITDA multiples. But beware: the window to capitalise on these lower multiples was short, with valuations bouncing back to their pre-crisis level relatively quickly.

M&A drives competitive advantage in a slow-growth environment

Even amidst economic turbulence, some commercial imperatives remain, such as diversifying away from failing products or services and gaining competitive advantage through new tech or IP. These imperatives may even become stronger, as revenues falter and margins are squeezed.

Diversification and competitive advantage can be achieved more rapidly through an acquisition than by organic growth, allowing the target’s operations to be immediately “plugged in”.

By way of example: at the zenith of the financial crisis in 2009, Pfizer’s snapped up Wyeth for $68.4 billion to offset the fact that their patents on several major medicines were nearing expiration. The deal also allowed Pfizer to diversify its pharmaceutical portfolio and strengthen its pipeline, with a particular emphasis on biopharmaceuticals and vaccines.

Due diligence takes on heightened importance

While the rewards of acquisition during an economic downturn can be high, so can the risks.

Even though valuations will drop, and many distressed but inherently viable businesses will come to market, not all deals will represent a good ROI. For this reason, thorough due diligence will take on heightened importance when looking at distressed assets.

Acquirers will want to look at all the typical symptoms of underlying health, such as cash flow and strength of the customer base/supply chain. They’ll also want to look at broader market and industry analysis to determine how the company will fare during a recovery.

Remember: some sectors are permanently changed by downturns. The financial sector is a case in point: the return on equity (ROE) for European banks has remained much lower than pre-crisis levels, hovering around 4–5%, compared to 15-17% pre-crisis. The manufacturing sector also had to adapt or die: companies have had to become more lean and cost-efficient, adopting just-in-time (JIT) inventory practices and investing in automation.

The lesson? Think carefully about whether your target has the resilience and wherewithal to emerge kicking from the current round of turbulence.

Selling during downturns

Unfortunately, the whims of the global economy do not always cater for business owners’ exit plans, with little things like recessions, fiscal policy and geopolitical upheaval often throwing a wrench in the works.

However, sometimes the most sensible business strategy is to throw in the towel, whatever the external environment. This might be due to factors of health, age, shareholder conflicts, or a simple loss of motivation.

Sellers ought to moderate their valuation expectations

Selling during a downturn, however, should come with moderated expectations. Valuation multiples are usually depressed, with sellers getting a lower ROI than they might have hoped for.

At the height of the fallout of the financial crisis, EBITDA multiples plummeted to a low of 6.5 in Q1 2009.

Ride the wave of industry consolidation before it passes

Downturns usually spur waves of industry consolidation, as the large players snap up distressed assets at lower prices.

See this recent headline from the Financial Times: ‘Housing market downturn pushes UK estate agents to consolidate’. Or this one: ‘Brookfield predicts consolidation in asset management amid downturn’. Or this one from 2008: ‘Consolidation: Slowdown boosts growth of M&A’.

Catching and riding any waves of industry consolidation before they pass by is crucial: waiting around can undermine smaller companies’ market share, revenues and margins, and leave them in a less competitive negotiating position. By contrast, going to market early in a consolidation phase is likely to produce a stronger valuation.

Creative deal structures help to bridge buyer-seller valuations

Turbulent economic times usually create the dreaded buyer-seller valuation gap, which in turn leads to increased use of creative deal structures such as earnouts, deferred consideration, seller financing like a seller’s note or seller rollover equity.

For example, SRS Acquiom reported that in 2023, the use of earnouts surged by approximately 62%, reflecting a widening gap in valuation expectations between buyers and sellers, amidst that year’s sky-high inflation and interest rates. Additionally, earnouts accounted for a record 40% of the total purchase price, the highest level ever recorded, highlighting the increased reliance on contingent payments to bridge these valuation differences.

An earnout involves structuring a portion of the purchase price based on the future performance of the target company. The seller receives additional payments if the business hits certain revenue, profit, or operational targets post-acquisition.

Conclusion

Uncertainty – the new normal?

A recent report from Bayes Business School indicates that the UK M&A market remains “remarkably robust” despite nearly a decade of political, economic, and social upheaval. Many investors, they suggested, are beginning to view uncertainty as the “new normal.”

The key takeaway? Downturns can present unique opportunities for strategically and financially strong companies, while financially distressed firms may opt to sell non-core assets, helping buyers to enhance their competitive position.

Meanwhile, turbulence creates favourable conditions for entrepreneurs in resilient sectors such as renewable energy, healthcare, government and defence contracting, and telecommunications to consider selling their businesses.